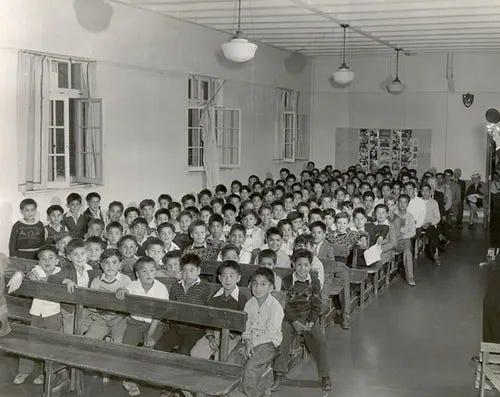

What Was the First Day of Residential School Like? Part 2

In most cases, what little was known about Indigenous culture and spirituality was looked down upon as heathenistic devil worship

In most cases, what little was known about Indigenous culture and spirituality was looked down upon as heathenistic devil worship

Verna Kirkness attended the Dauphin, Manitoba, residential school. On arrival at that school after a lengthy train trip, she said she was stripped of all her clothing. “They didn’t tell me that they were gonna do that. And they poured something on my head, I don’t know what it was, but it didn’t smell too good. To this day, I don’t know what it is. But from my understanding, from people explaining it to me, it was coal oil, or some, some kind of oil, and they poured that on my head, and then they cut my hair really, really short. And then, and when we, we sat, I remember sitting, I don’t know it’s, it looked like a picnic table. It was in the corner, I think it was in the corner, and I sat there. I was looking around, and I was looking for my sister. And then I, and then I think we were given a doughnut, or some kind of pastry, and then we were sent to bed. And I remember my first bed. It was right by the door. And then as when you walk in, it was on your right-hand side, and I was on the top bunk, the first bunk bed, I was on the top bunk, and that’s my first, my very first night there.”[17]

At the Blue Quills school, Alice Quinney and the other recently arrived students were told they were to be given a bath. “I had never been naked in front of anybody ever before, except my mom, who would give us a bath in, in the bathtub at home, in a, in a round tub, you know the old round tubs that they had, the steel tubs, that’s the kind of, you know. And so that was hard too, they told us before, when we went down to the bathroom, we all had to strip, and they put this nasty smelling stuff in our hair, for bugs, they said, if we had brought any bugs with us. So, they put all that stuff, and some kind of powder that smelled really bad. And then we were, we had to take off all our clothes, and, and go in, in the showers together.”[18]

On her arrival at the Alberni, British Columbia school, Lily Bruce was separated from her brother and taken to the girls’ dormitory. “I had to take a bath, and it was late at night, and I kept crying, and she was calling me a crybaby, and just kept yelling at me, and said if I woke up anybody, I was in deep trouble. ‘And if your mother and dad really cared about you, they wouldn’t have left you here.’ [audible crying] And then she started pulling my long hair, checking for lice. [audible crying] After she checked my hair and shampooed my hair, I had to have vinegar put in there, and being yanked around in that tub, too, had to wash every part of my body or else they were gonna do it, and I didn’t want, I didn’t want them to touch me.”[19]

Helen Harry’s hair was cut on her arrival at the Williams Lake, British Columbia, school. “And I remember not wanting to cut my hair, because I remember my mom had really long hair, down to her waist. And she never ever cut it, and she never cut our hair either. All the girls had really long hair in our family. And I kept saying that I didn’t want to cut my hair, but they just sat me on the chair and they just got scissors and they just grabbed my hair, and they just cut it. And they had this big bucket there, and they just threw everybody’s hair in that bucket. I remember going back to the dorm and there was other girls that were upset about their hair. They were mad and crying that they had to get their hair cut. And then when that was all done, we were made to wash our hair out with some kind of shampoo. And I just remember it smelling really awful. The smell was bad. And this is, I think it had something to do with delousing people, I’m not sure.”[20]

In 1985, Ricky Kakekagumick was one of a group of children who were own to the Poplar Hill, Ontario school. On arrival, the boys and girls were separated and marched to their dormitories. “When we got there, there’s staff people there, Mennonite men. They’re holding towels. So, we just put our luggage down on the floor there, and they told us, ‘Wet your hair.’ I had long hair, like, I was an Aboriginal teenager, I grew long hair. So, they told us, ‘Wash your hair.’ Then they had this big bottle of chemical. I didn’t know what it was. It looked like something you see in a science lab. So, they were pumping that thing into our hand, ‘And put it all over your head,’ they said. ‘So, it will, this will kill all of the bugs on your head.’ Just right away they assumed all of us had bugs, Aboriginal. I didn’t like that. I was already a teenager. I was already taking care of myself. I knew I didn’t have bugs. But right away they assumed I did because I’m Aboriginal. So after we washed our hair, everybody went through that, then we went to the next room. Then that’s where I see a bunch of hair all over the floor. I see a guy standing over there with those clippers, the little buzz, was buzzing students. I kept on moving back. There was a line there. I kept going back. I didn’t want to go. But it came down to the end, I had no choice, ’cause everybody was already going through it, couldn’t go behind anybody no more. So, I made a big fuss about it, but couldn’t stop them. It was a rule. So, they, they gave me a brush, and they gave us one comb, too, and told us this is your comb, you take care of it.”[21]

As a child, Bernice Jacks had been proud of her long hair. “My mom used to braid it and French braid it and brush it. And my sister would look after my hair and do it.” But, on her arrival at residential school in the Northwest Territories, a staff member sat her on a stool and cut her hair. “And I sat there, and I could hear, I could see my hair falling. And I couldn’t do nothing. And I was so afraid my mom … I wasn’t thinking about myself. I was thinking about Mom. I say, ‘Mom’s gonna be really mad. And June is gonna be angry. And it’s gonna be my fault.’”[22]

Victoria Boucher-Grant was shocked by the treatment she received upon enrolment at the Fort William, Ontario school. “And they, they took my braids, and they chopped my, they didn’t even cut it, they just, I mean style it or anything, they just took the braid like that, and just cut it straight across. And I remember just crying and crying because it was almost like being violated, you know, like when you’re, when I think about it now it was a violation, like, your, your braids got cut, and it, I don’t know how many years that you spent growing this long hair.”[23]

Elaine Durocher found the first day at the Roman Catholic school in Kamsack, Saskatchewan to be overwhelming. “As soon we entered the residential school, the abuse started right away. We were stripped, taken up to a dormitory, stripped. Our hair was sprayed.… They put oxfords on our feet, ’cause I know my feet hurt. They put dresses on us. And were made, we were always praying, we were always on our knees. We were told we were little, stupid savages, and that they had to educate us.”[24]

Brian Rae said he and the other boys at the Fort Frances, Ontario school were given a physical inspection by female staff. “You know, to get stripped like that by a female, you know, you don’t even know, ’cause, you know, it was embarrassing, humiliating. And, and then she’d have this, you know, look or whatever it was in her eyes, eh, you know. And then she would comment about your private parts and stuff like that, eh, like, say, ‘Oh, what a cute peanut,’ and you know, just you know kind of rub you down there, and, and then, you know, just her eyes, the way she looked. So that kind of made me feel, feel all, you know, dirty and, you know, just, I don’t know, just make me feel awful I guess because she was doing that. And then the others, you know, the other kids were there, you know, just laughing, eh, that was common. So, I think that was the first time I ever felt humiliated about my sexuality.”[25]

Julianna Alexander found the treatment she received upon arrival at the Kamloops, British Columbia school demeaning. “But they made us strip down naked, and I felt embarrassed, you know. They didn’t, you know I just thought it was inappropriate, you know, people standing there, watching us, scrubbing us and everything, and then powdering us down with whatever it was that they powdered us with, and, and our hairs were covered, you know, really scrubbed out, and then they poured, I guess what they call now coal oil, or whatever that was, like, some kind of turpentine, I’m not sure what it was, but anyway, it really stunk.”[26]

On their arrival at residential school, students often were required to exchange the clothes they were wearing for school-supplied clothing. This could mean the loss of homemade clothing that was of particular value and meaning to the students. Murray Crowe said his clothes from home were taken and burned at the school that he attended in northwestern Ontario.[27]

When Wilbur Abrahams’s mother sent him to the Alert Bay school, she outfitted him in brand-new clothes. When he arrived at the school, he and all the other students were lined up. “They took us down the hall, and we were lined up again, and, and I couldn’t figure out what we were lined up for, but I dare not say anything. And pretty soon it’s my turn, they told me to take all of my clothes off, and, and they gave me clothes that looked like they were second-hand, but they were clean, and told me to put those on, and that was the last time I saw my new clothes. Dare not ask questions.”[28]

John B. Custer said that upon arrival at the Roman Catholic school near The Pas, Manitoba, all the students had their personal clothing taken away. “And we were dressed in, we were all dressed the same. Like, we had coveralls on. I remember when I went over there, I had these beaded moccasins. As soon as I got there, they took everything away.”[29]

Elizabeth Tapiatic Chiskamish attended schools in Québec and northern Ontario. She recalled that when she arrived at school, her home clothing was taken from her. “The clothes we wore were taken away from us too. That was the last time we saw our clothes. I never saw the candy that my parents packed into my suitcase again. I don’t know what they did with it. It was probably thrown away or given to someone else or simply kept. When I was given back the luggage, none of things that my parents packed were still in there. Only the clothes I wore were still sometimes in the suitcase.”[30]

Phyllis Webstad recalled that her mother bought her a new shirt to wear on her first day at school at Williams Lake. “I remember it was an orange shiny colour. But when I got to the Mission it was taken and I never wore it again. I didn’t understand why. Nothing was ever explained why things were happening.”[31] Much later, her experience became the basis for what has come to be known as “Orange Shirt Day.” Organized by the Cariboo Regional District, it was first observed on September 30, 2013. On that day, individuals were encouraged to wear an orange shirt as a memorial of the damage done to children by the residential school system.[32]

When Larry Beardy left Churchill, Manitoba for the Anglican school in Dauphin, he was wearing a “really nice, beautiful beaded” jacket his mother had made. “I think it was a caribou, a jacket, and she, she made that for me because she knew I was going to school.” Shortly after he arrived at school, “all, all our clothes were taken away. My jacket I had mentioned was gone. And everybody was given the same, the same kind of clothing, with the old black army boots, we used to call them, and slacks.”[33]

Ilene Nepoose recalled that the belongings she took to the Blue Quills residential school were taken away from her upon arrival. “I even brought my own utensils [laughing] and I never saw those things again, I often wonder what happen to them. But I remember at the end of the first school, the first year—they take our personal clothes away and they give us these dresses that are made out of our sacks.” When she was to return home at Christmas time, the staff could not find the clothes she had worn to come to school. “I saw them on this other girl and I told the nuns that she was wearing my dress and they didn’t believe me. So, that girl ended up keeping my dress and I don’t remember what I wore, it was probably a school dress. But, that really bothered me because it was my own, like my mom made that dress for me and I was very proud of it and I couldn’t—I wasn’t allowed to wear that again.”[34]

Nick Sibbeston attended the Fort Providence school for six years. He was enrolled in the school after his mother was sent to the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton for tuberculosis treatment. The only language he spoke was Slavey (Dene); the only language the teachers spoke was French. “On arrival you’re given a bath and you’re de-liced and you’re given a haircut and all your clothes are taken away. I know I arrived with a little bag that my mother had filled with winter things, you know, your mitts … but all of that was taken away and put up high in a cupboard and we didn’t see it again ’til next June.”[35]

When Carmen Petiquay went to the Amos, Québec school, the staff “took away our things, our suitcases, my mother had put things that I loved in my suitcase. I had some toys. I had some clothing that my mother had made for me, and I never saw them again. I don’t know what they did with those things.”[36]

Martin Nicholas of Nelson House, Manitoba went to the Pine Creek, Manitoba school in the 1950s. “My mom had prepared me in a Native clothing. She had made me a buckskin jacket, beaded with fringes.… And my mom did beautiful work, and I was really proud of my clothes. And when I got to residential school, that first day I remember, they stripped us of our clothes.”[37]

To Be Continued…

Darren Grimes

Footnotes at the end of Part 4

What Was the First Day of Residential School Like? Part 3

And even right from day one, I remember they took everything I had

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indigenous Opinions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.