What Was the First Day of Residential School Like? Part 1

What bonds are interrupted when a young child is taken from the family home and settled into government and/or religious institutions?

The first day of school can be a stressful and overwhelming day for a child. Even if you don’t have children of your own that you’ve seen a little stressed or upset about heading back to school after the summer break, you can probably remember sometime in the not-so-distant past that you had these feeling of apprehension towards school life yourself. I was certainly no fan of school. I hated the early mornings and how it stole away the best hours of the day. The best hours of the day seem somewhat paltry in comparison to the best years of a child’s life. What bonds are interrupted when a young child is taken from the family home and settled into government and/or religious institutions?

While first nations children in Canada are not the first, nor the last in history to be raised out of the family home, the fact that they did so in places that had little to no knowledge of their cultures, history, or languages was especially destructive. In most cases, what little was known about Indigenous culture and spirituality was looked down upon as heathenistic devil worship. This is evidenced by the banning of indigenous religious ceremonies like the Potlach and the Sun Dance and the refusal to allow students in Residential schools to communicate with one another in their native languages.

Nellie Ningewance was raised in Hudson, Ontario, and went to the Sioux Lookout, Ontario, school in the 1950s and 1960s. Her parents enrolled her in the school at the government’s insistence. She told her mother she did not want to go. “But the day came where we, we were all bussed out from Hudson. My mother told me to pack my stuff; a little bit of what I needed, what I wanted. I remember I had a little doll that my dad had given me for a Christmas present. And I had a little trunk where I made my own doll clothes. I started sewing when I was nine years old. My mom taught us all this though, sewing. So I used to make my own doll clothes; I packed those up, what I wanted. I guess I had mixed feelings. I was kind of excited to go away to go to school. My mom tried to make it feel comfortable for me and I know it was hard for her and hard for me. But when the time we were ready to leave, they had a bus; and there was lots of people with their kids waiting to leave. And I made sure I, I was the last one to board the bus, ’cause I didn’t want to go. I remember hugging my mom, begging her, getting on the bus; waving at them as they were going, pulling away. I don’t remember how long the ride was from Hudson to Pelican at the time, but it seemed like a long ride.… When we arrived there, again I was, I made sure I was the last one to get on the bus. And when I arrived there, a guy standing at the bottom there helping all the students to get on the bus, reaching out his hand like this; I didn’t even want to touch him. I didn’t even want to get off. I’m hanging to the bar; I didn’t want to get off. To me he looked so ugly. He was dark, short, and he was trying to coax me to come down the stairs and to help me get off the bus. I hang onto the bus and they had to force me and pull me down to get off the bus. The next three days I guess was sort of, like it was like floating.… I remember crying then calming down for a while, then crying again…. When we arrived we had to register that we had arrived then they took us to cut our hair. The next thing was to get our clothes. They gave us two pairs of jeans, two pairs of tee-shirts, two church dresses, they were beautiful dresses; two pairs of shoes, two pairs of socks, two pairs of everything. And we had a number; they gave us a number and that number was tied in our, in all our clothes; our garments, our jackets, everything was numbered. After that we were told to be in the, go in the shower; at least fifteen of us girls all in one shower. We were told to strip down and, with all the other girls; and that was not a comfortable feeling. And for me I guess it was violating my privacy. I didn’t even want to look at anybody else. It was hard. After that, they gave us our toothbrushes to brush our teeth. And they asked us to put our hands out and they put some white dry powder stuff on our hands. I didn’t know what it was. I smelt it, but now today I know it was baking soda. I didn’t realize what it was then.”[1]

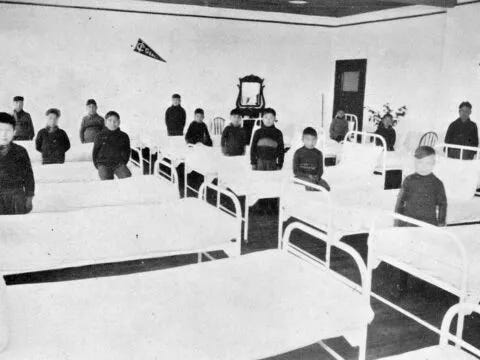

Campbell Papequash had been raised by his grandfather. When his grandfather died in 1946, Papequash “was apprehended by the missionaries and taken to residential school. When I was taken to this residential school you know I experienced a foreign way of life that I really didn’t understand. I was taken into this big building that would become the detention of my life and the fear of life. When I was taken to that residential school you know I see these ladies, you know so stoical looking, passionate-less and they wore these robes that I’ve never seen women wear before, they only showed their forehead and their eyes and the bottom of their face and their hands. Now to me that is very fearful because you know there wasn’t any kind of passion and I could see, you know, I could see it in their eyes. When I was taken to this residential school, I was taken into the infirmary but before I entered the infirmary, you know, I looked around this big, huge building, and I see all these crosses all over the walls. I look at those crosses and I see a man hanging on that cross and I didn’t recognize who this man was. And this man seemed dead and passionate-less on that cross. I didn’t know who this man was on that cross. And then I was taken to the infirmary and there, you know, I was stripped of my clothes, the clothes that I came to residential school with, you know, my moccasins, and I had nice, beautiful long hair and they were neatly braided by mother before I went to residential school, before I was apprehended by the residential school missionaries. And after I was taken there, they took off my clothes and then they deloused me. I didn’t know what was happening, but I learned about it later, that they were delousing me; ‘the dirty, no-good-for-nothing savages, lousy.’ And then they cut off my beautiful hair. You know and my hair, my hair represents such a spiritual significance of my life and my spirit. And they did not know, you know, what they were doing to me. You know and I cried, and I see them throw my hair into a garbage can, my long, beautiful braids. And then after they deloused me then I was thrown into the shower, you know, to go wash all that kerosene on my body and on my head. And I was shaved, bald-headed. And then after I had the shower, they gave me these clothes that didn’t fit, and they gave me these shoes that didn’t fit, and they all had numbers on them. And after the shower then I was taken up to the dormitory. And when I went to, when I was taken up to this dormitory, I seen many beds up there, all lined up so neatly and the beds made so neatly. And then they gave me a pillow, they gave me blankets, they gave me sheets to make up my bed. And lo and behold, you know, I did not know how to make that bed because I came from a place of buffalo robes and deer hides and rabbit skins to cover with, no such thing as a pillow.”[2]

Marthe Basile-Coocoo recalled feeling a chill on first seeing the Pointe Bleue, Québec, school. “It was something like a grey day, it was a day without sunshine. It was, it was the impression that I had, that I was only six years old, then, well, the nuns separated us, my brothers, and then my uncles, then I no longer understood. Then that, that was a period there, of suffering, nights of crying, we all gathered in a corner, meaning that we came together, and there we cried. Our nights were like that.”[3]

Louise Large could not speak any English when her grandmother took her to the Blue Quills, Alberta, school in the early 1960s. “My grandma and I got into this black car, and I was kind of excited, and I was looking at the window and look. I’d never rode in a car before, or I might have, but this was a strange person. I went to, we drove into Blue Quills, and it was a big building, and I was in awe with the way it looked, and I was okay ’cause I had my grandma with me, and we got off, and we went up the stairs. And that was okay, I was hanging onto my grandma, I was going into this strange place. And, and we walked up the stairs into the building, and down the hallway, going to the left, and there was a room there, and two nuns came.”

As was often the case, she was not used to seeing nuns dressed in religious habits. “I didn’t know they were nuns. I don’t know why they were dressed the way they were. They had long black skirts, dresses, and at that time they looked weird ’cause they had these little weird hats and a veil, kind of like a black bridesmaid or something, and they were all smiling at me.” She was shocked to discover she was going to be left at the school. The nuns had to hold Louise tight to stop her from trying to leave with her grandmother. “And I wasn’t aware at that time that my grandma was gonna leave me there. I’m not ever sure how she told me, but they started holding me and my grandma left and I started fighting them because I didn’t want my grandma to leave me, and, and I started screaming, and crying and crying, and it must have been about, I don’t know, when I look back, probably long enough to know that my grandma was long gone. They let me go, and they started yelling at me to shut up, or I don’t know, they had a real mean tone of voice. It must have been about, when I think about it, it was in the morning, and I just screamed and screamed for hours. It seemed like for hours. They all ran down to the water’s edge to get on the float plane that would take them to school. On their arrival, they were taken to the school by the same truck that was used to haul garbage to the local refuse site. From that point on, the experience was much more somber. And I can still recall today the, the quiet, the quiet, and all the sadness, the atmosphere, as we entered that big stone building. The excitement in the morning was gone, and everybody was quiet because the … senior students that had been there before knew the rules, and us newcomers were just beginning to see, and we were little, we were young. I remember how they took our clothes, the clothes that we wore when we left, and they also cut our hair. We had short hair from there on. And they put a chemical on our hair, which was some kind of a white powder.”[4]

Linda Head was initially excited about the prospect of a plane trip that would take her to the Prince Albert, Saskatchewan school. “My dad kissed me, and up I went, I didn’t care [laughs] ’cause this was something new for me.” The plane landed on the Saskatchewan River. “There was a, a car waiting for us, or the truck. But I got into the car, and the boys were in the truck, like an army, an army truck. They stood outside the, outside, you know, at the back, not inside. They gave us, told us which dorm to go, and, and there was a person standing, but the kids were, you know, lining up, and this person took me to the line. And when the line was full, I guess when we were, they took us to the dorm…. We had our numbers, and a bed number. And she told us to settle down. Well, I wasn’t understanding this ’cause it was English, but I followed, you know, watch, watch everybody, and … she took my hand, and guided me to the bed, and the number showed me what number I was, number four, and we had to find number four. So that’s how it was then. My stuff, I had to set it down, then I, I was under, under the bed, not the higher up, I had the lower bed. So, I was just lying around there … the music was loud, the radio. Everybody was talking in Cree, some of them in Cree, some of them in English, well a little bit of English. And my cousins … we were in together some of them, some of us at the same age, so they came over and talked to me. I said, ‘Well, here we are.’ Here I was missing home already.”[5]

Gilles Petiquay, who attended the Pointe Bleue, Québec, school, was shocked by the numbering system at the school. “I remember that the first number that I had at the residential school was 95. I had that number—95—for a year. The second number was number 4. I had it for a longer period of time. The third number was 56. I also kept it for a long time. We walked with the numbers on us.”[6]

Mary Courchene grew up on the Fort Alexander Reserve in Manitoba. Her parents’ home was just a five-minute walk away from the Fort Alexander boarding school. “One morning my mom woke us up and said we were going to school that day and then she takes out new clothes that she had bought us and I was just so happy, so over the moon. And, she was very, very quiet. And she was dressing us up and she didn’t say too much. She didn’t say, “Oh I’ll see you,” and all of that. She just said, she just dressed us up with, with no comment. And then we left; we left for the school.” When the family reached the school, they were greeted by a nun. Mary’s brother became frightened. Mary told him to behave himself. She then turned around to say goodbye to her mother, but she was gone. Her mother had gone to residential school as a child. “And she could not bear to talk to her children and prepare her children to go to residential school. It was just too, too much for her.” Courchene said that on that day, her life changed. “It began ten years of the most miserable part of my life, here on, here, in the world.”[7]

Roy Denny was perplexed and frightened by the clothing that the priests and sisters wore at the Shubenacadie school. “And we were greeted by this man dressed in black with a long gown. That was the priest, come to find later. And the nuns with their black, black outfits with the white collar and a white, white collar and, like a breast plate of white. And their freaky looking hats that were, I don’t, I couldn’t, know what they remind me of. And I didn’t see, first time I ever seen nuns and priests. And they, and they were speaking to me, and I couldn’t understand them.” He had not fully understood that his father was going to be leaving him at the school. “So when my father left I tried to stop him; I tried, I tried to go, you know, tried to go with him, but he said, ‘No, you got to stay.’ That was real hard.”[8]

Archie Hyacinthe said he was unprepared for life in the Catholic school in Kenora. “It was almost like we were, you know, captured, or taken to another form of home. Like I said, nobody really explained to us, as if we were just being taken away from our home, and our parents. We were detached I guess from our home and our parents, and it’s scary when you, when you first think, think about it as a child, because you never had that separation in your lifetime before that. So that was the, I think that’s when the trauma started for me, being separated from my sister, from my parents, and from our, our home. We were no longer free. It was like being, you know, taken to a strange land, even though it was our, our, our land, as I understood later on.”[9]

Dorene Bernard was only four and a half years old when she was enrolled in the Shubenacadie residential school. She had thought that the family was simply taking her older siblings back to the school after a holiday. “I remember that day. We went down there to take my sister and brother back. My father and mom went in to talk to the priest, but they were making plans to leave me behind. But I didn’t know that, so I went on the girls’ side with my sister and she told me after couple hours went by that they had already left. I would say it was pretty difficult to feel that abandoned at four and a half years old. But I had my sister, my older sister Karen, she took care of me the best way she could.”[10

When parents brought their children to the school themselves, the moment of departure was often heartbreaking. Ida Ralph Quisess could recall her father “crying in the chapel” when she and her siblings were sent to residential school. “He was crying, and that, one of the, these women in black dresses, I later learned they were sisters, they called them, nuns, the Oblate nuns, later, many years after I learned what their title was, and the one that spoke our language told him, ‘We’ll keep your little girls, we’ll raise them,’ and then my father started to cry.”[11]

Vitaline Elsie Jenner resisted being sent to school. “And I didn’t want to go to the residential school. I didn’t realize what I was going to come up against upon being there. I resisted. I cried and I fought with my mom. My mom was the one that took us there and dragged, actually just about dragged me there, because of my resistance, not wanting, I hung onto everything that was in the way, resisting.” The separation at the Fort Chipewyan school in northern Alberta was traumatic. “And so when I went upon, when we went into the residential school, it was in the parlour, and there was a nun that was receiving the students that were going into the residential school, and I, you know, like I hung onto my mom as tight as I can. And what I remember was she had taken my hand, and what she did, what my mom did, I, I don’t remember the rest of my siblings, it’s just like I kind of blocked out, because that was traumatic already for me as it was, being taken there, you know, and this great big building looked so strange and foreign to me, and so she took my hand, and forcefully put my hand in the nun’s hand, and the nun grabbed it, so I wouldn’t run away. So, she grabbed it, and I was screaming and hollering. And in my language I said, ‘Mama, Mama, kâya nakasin’ and in English it was, ‘Mom, Mom, don’t leave me.’ ’Cause that’s all I knew was to speak Cree. And so the nun took us, and Mom, I, I turned around, and Mom was walking away. And I didn’t realize, I guess, that she was also crying.”[12]

Lily Bruce’s parents were in tears when they left her and her brother at the Alert Bay, British Columbia, school. “And our parents talked to the principal, and, and then Mom was in tears, and I remember the last time she was in tears was when my brother Jimmy was put in that school. And her and Dad went through those double doors in the front, and the principal and his wife were saying that they were gonna take good care of us, that they were gonna treat us like they were our new parents, and not to worry about us, and just bringing our hopes up, and so Mom and Dad left. And I grabbed my brother, and my brother held me, we just started crying. [audible crying] We were hurt because Mom and Dad left us there.”[13]

Margaret Simpson attended the Fort Chipewyan school in the 1950s. She was initially excited to be going to residential school because she would be going with her brother George. “I was happy I was going with him, and my dad took us and there we’re walking to the, to this big orange building. It was in, and we got there, and I was so happy ’cause I was going to go in here with George and I was going to be with him but you know this was far as it was going to go once we made it in there. He went one way, and I was calling him and this other nun took me the other way, so we separated right there. Right from there I was wondering what is happening here? I was so lost, I was so lost. And they brought me downstairs and then I looked and all of a sudden, I seen my dad passing on the other side of the fence, he was walking. I just went running, I seen the door over there and I went running I was going to go see my dad over there. But they stopped me, and I was crying and I was telling my dad to come and he didn’t hear me and I was wondering what is happening, I don’t even know.”[14]

The rest of a new student’s first day is often remembered as being invasive, humiliating, and dehumanizing. Her first day at the Catholic school in Kenora left Lynda Pahpasay McDonald frightened and distressed. “And I had, I must have had long hair, like long, long hair, like, and my brothers, even my brother had long hair, and he looked like a little girl. Then they took us into this, it was like a greeting area, we went in there, and they kind of counted us, me and my siblings. And I was hanging onto my sister, and she told me not to cry, so don’t cry, you know, you just, you listen. She was trying to tell me, and I was crying, and of course me and my sister were crying, there’s three of us, we’re just a year apart. Me, Barbara, and Sandy were standing there, crying. She was telling us not to cry, and, and just do what we had to do. And, and I remember having, watching my brother being, like, taken away, my older brother, Marcel. They took him, and he had long hair also. And we were taken upstairs, and they gave us some clothing, and they put numbers on our clothes. I remember there’s little tags in the back, they put numbers, and they told us that was your number. Well, I can’t remember my number. And, and we seen the nuns. They had these big black outfits, and they were scary looking, I remember. And of course they weren’t really, they looked really, I don’t know, mean, I guess. And, and we, they took us upstairs, I remember that, and they gave us these clothes, different clothes, and they took us to another room, then they kind of, like, and they took our old clothes, they took that, and they made us take a bath or a shower. I think it was a bath at that time. After we came out, and they washed our hair, and I don’t know, they kind of put some kind of thing on our hair, like, you know, our heads, and they’re checking our hair and stuff like that. And then they took us to this chair, and they put a white cloth over our shoulders, and they started cutting our hair. And you know they cut real straight bangs, and real short hair, like, it was real straight haircuts. I didn’t like the fact that they cut off all our hair. And same with my brother, they had, they cut off all of, most of his hair. They had a, he had a brush cut, like.”[15]

When Emily Kematch arrived at the Gordon’s, Saskatchewan school from York Landing in northern Manitoba, her hair was treated with a white powder and then cut. “And we had our clothes that we went there with even though we didn’t have much. We had our own clothes but they took those away from us and we had to wear the clothes that they gave us, same sort of clothes that we had to wear.”[16]

To Be Continued….

Darren Grimes

Footnotes at the end of Part 4

What Was the First Day of Residential School Like? Part 2

In most cases, what little was known about Indigenous culture and spirituality was looked down upon as heathenistic devil worship

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indigenous Opinions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.