Wasted Nations - The Indigenous Suicide Epidemic

Suicide and Self-harm is the leading cause of death for Indigenous Canadians Under the Age of 44

The suicide problem among Indigenous populations in Canada is an ongoing problem of epidemic proportions. Across the country, suicide and self-inflicted injury is the leading cause of death for First Nations people below the age of 44. Some studies show young indigenous males are 10 times more likely to kill themselves than their non-indigenous counterparts, while young indigenous females are up to 21 times more likely. It is important to note that before the 19th century suicide was extremely rare in North American Native communities. The culture shock that ensued with the arrival of the European explorers coupled with the actual institutionalized racism inherent in the Canadian government’s policies, resulted in a steady increase of suicide in the 20th century which has continued until the present day.

Decades of cultural and physical child abuse have taken their toll to such an extent that the government of Canada was forced to take notice. The government study from 2011-2016 reported:

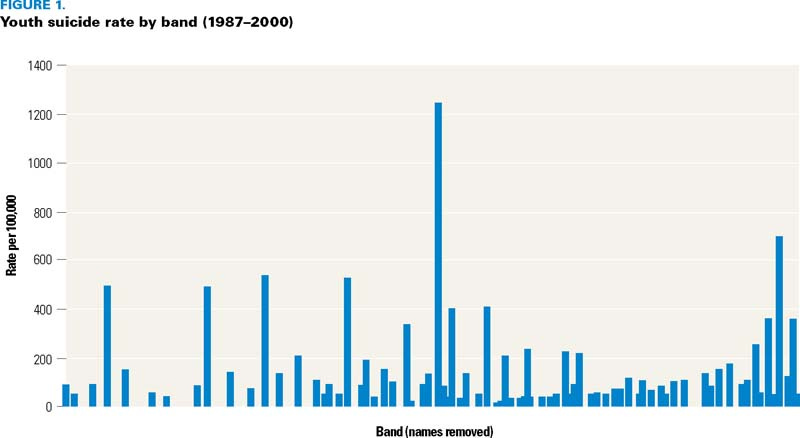

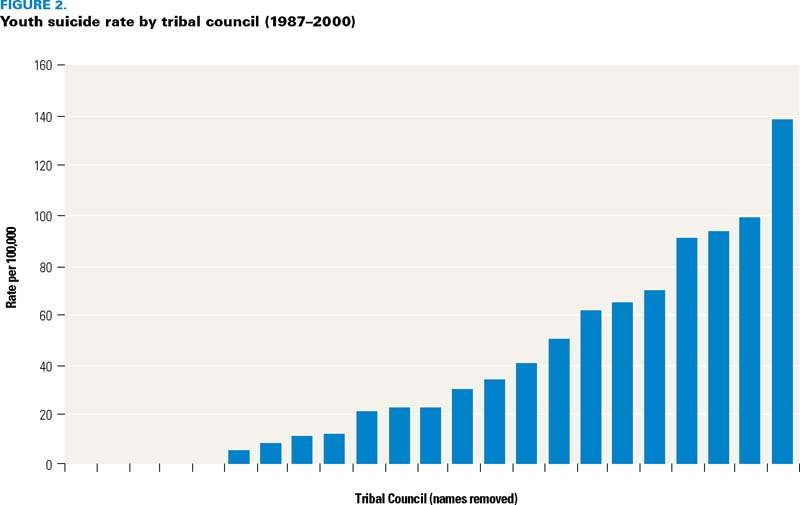

Suicide rates among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit were significantly higher than the rate among non-Indigenous people. The rate among First Nations people (24.3 deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk) was three times higher than the rate among non-Indigenous people (8.0 deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk). Among First Nations people living on reserve, the rate was about twice as high as that among those living off reserve. However, suicide rates varied by First Nations band, with just over 60% of bands having a zero suicide rate. The rate among Métis (14.7Note E: Use with caution deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk) was approximately twice as high as the rate among non-Indigenous people. Among Inuit, the rate was approximately nine times higher than the non-Indigenous rate (72.3 versus 8.0 deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk). Suicide rates and disparities were highest in youth and young adults (15 to 24 years) among First Nations males and Inuit male and females.

Suicide rates have consistently been shown to be higher among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada than the rate among non-Indigenous people; however, suicide rates vary by community, Indigenous group, age group and sex. The historical and ongoing impacts of colonization, forced placement of Indigenous children in residential schools in the 19th and 20th centuries, removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities during the “Sixties scoop” and the forced relocation of communities has been well documented. These resulted in the breakdown of families, communities, political and economic structures; loss of language, culture and traditions; exposure to abuse; intergenerational transmission of trauma; and marginalization, which are suggested to be associated with the high rates of suicide.

Trauma inflicted at such young ages creates cyclical and toxic cycles that will continue to manifest in different, but predictably destructive ways.

While suicide among Indigenous people has been examined previously, studies were based on a decades-old cohort or used an area-based geozones approach. Past studies also examined suicides among only one or two Indigenous groups using the same methodology. Finally, they did not examine suicide among Indigenous people for some geographies such as on and off reserve, rural areas and small, medium and large population centres.

The high rates of suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit has been suggested to be the result of historical and intergenerational trauma experienced as a result of colonization and on-going marginalization. Colonialism has also been suggested to broadly impact Indigenous peoples’ health by producing social, political and economic inequalities that, in turn, play a role in the development of conditions related to poorer health. Many historical and contemporary factors have been associated with suicide among Indigenous people in Canada. These include acculturation stresses like

(1) loss of land, traditional subsistence activities and control over living conditions;

(2) suppression of belief systems and spirituality;

(3) weakening of social and political institutions;

(4) racial discrimination; and

(5) marginalization.

Of particular concern is the high rate of suicide among Indigenous children under 15. The suicide rate among First Nations boys, nationally, was four times higher than among non-Indigenous boys. It was ten times higher among First Nations boys living on reserve. As with other national trends, this rate may obscure regional differences. Previously reports have suggested that in some remote First Nations communities in Ontario, under-15 suicide rates were nearly 50 times higher than non-Indigenous rates. And, among Inuit communities of Nunatsiavut, the age-specific disparity was largest among 10 to 19-year-olds relative to their non-Indigenous counterparts outside Inuit Nunangat. Also, rate of death by suicide among Inuit children 10 to 14 years of age appears to be increasing since 1989 although significant fluctuations are seen across time. In line with these rates among children, suicidal ideation among grade 5 to 8 school children in Saskatoon was nearly twice as high among Indigenous children as non-Indigenous children after accounting for mental health, cognitive abilities and bullying experiences. While risk factors for suicide among children are numerous and complex, a recent report suggests that Inuit children and youth in Nunavut experience a lack of mental health services that are specific to them, culturally relevant and of adequate quality. (Statistics Canada, 2018. p. 12)

Millions of dollars are spent every year to fight suicide epidemics amongst Indigenous peoples in Canada but the federal government collects little to no data about the actual suicide rates.There is a serious lack of record keeping by all levels of governments and coroners’ offices when it comes to suicide deaths of Indigenous people, APTN Investigates confirmed by requesting data from each province. Cindy Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, said she is troubled the federal government isn’t tracking suicide data. “I’m disappointed that we’re still not at a place were we’re keeping track of the number of attempts and deaths by suicide,” said Blackstock.

Some bands are undoubtedly suffering at higher rates than others, sometimes exponentially . What is being done different ? How are the Bands with the lowest rates of suicide avoiding the pitfalls that some of the less fortunate are falling into, and what knowledge can be shared in the interest of saving lives? If one thing has been made clear in the last 150 years it is that we cannot wait for the”help” of the governments if we expect this problem to be solved before it’s too late. If we continue to ignore the century and a half of cultural and (arguably) actual genocide perpetuated on the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, most of all on Indigenous children, we will continue to fall short in change.

Indigenous suicide is not just a mental-health problem, conditions on reserves often lag behind those in the rest of Canada in more respects than just suicide and health: Unemployment, lack of access to education and substandard infrastructure are growing factors as well. Five generations of residential schools traumatizing, indoctrinating, assimilating, and abusing Indigenous children evolved into the mass seizure and removal of children from Indigenous homes via child welfare during the sixties scoop and continues today.

How many generations have been crippled with suicidal depression due to the governments crimes against Indigenous children and families? A suicide epidemic, a substance abuse epidemic, a child welfare epidemic, a poverty epidemic and a missing and murdered Indigenous women epidemic.

How much is to much?

When is enough, enough?

Darren Grimes

These numbers are staggering. 50x higher indigenous teen deaths in rural areas in a time where society plays lip-service to indigenous rights and "celebrates" indigenous thinking...where will the future indigenous thinkers come from?

What the empire did to the First Nations, they now are trying with the rest of us.