Our Home and (Native?) Land - Part 6 “Let them Rob me”

Treaty No. 1 was made with the understanding that the Treaty would be in place for “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the river flows...

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 marked the beginning of a process where Europeans made treaties with Indigenous nations. The British crown instructed settlers on how to establish their lives on the land, but only the British crown had the authority to “negotiate” land arrangements with Indigenous nations. Settlers, on the other hand, could obtain land possession from colonial authorities.

The first treaty in Manitoba was the Peguis – Selkirk Treaty of 1817, where Chief Peguis and his people on the Red River entered into a relationship with Lord Selkirk. This treaty aimed to strengthen the legitimacy of Selkirk's colony, which faced questions about land rights from Indigenous communities in the area.

Similar to other treaties, difficulties in interpreting the Selkirk Treaty arose soon after its signing. The Hudson Bay Company claimed that the lands mentioned in the treaty were ceded and surrendered to them as the rightful owners of the entire region, without having made any land arrangements with Indigenous peoples. However, the Indigenous perspective has always been rooted in the concept of sharing the land for mutual benefit, as the idea of owning land as property was foreign to them. This calls to question today whether the existing Indigenous cultures had any real understanding of the implications of what they were signing. Many of the signatories resulting in a simple '“X”.

In the 1870s, the Canadian government sought to expand and settle the western regions, and extending the railroad was crucial to British Columbia's agreement to join Canada. The government negotiators were determined to secure signatures on the treaty documents by any means necessary. Indigenous signatories anticipated change and aimed to negotiate terms that would allow them to sustain their livelihoods in the new order. Drawing from their experiences with the Selkirk Treaty, they chose to emphasize the idea of sharing the land and maintaining a relationship for mutual benefit. However, the government negotiators perceived the arrangement as a cession and surrender of Indigenous lands.

Currently, Canada maintains the position that the land was ceded and surrendered through historic treaties, with the Crown receiving large areas of land in exchange for reserve lands and other benefits. Reserve lands that are in fact, still officially under the ownership the Canadian Government.

Despite differing interpretations of the treaties, there is still hope for reconciliation and agreement among all parties. In 2006, independent and "neutral" treaty commissions were established in Manitoba and Saskatchewan to facilitate discussions, public education, and research on treaty-related matters. It is recognized that the Treaty relationship is dynamic and will continue to evolve over time, providing a pathway for potential future revisions and mutual understanding.

Terms of Treaty 1

Treaty 1 was signed by government agents Lieutenant-Governor Adams G. Archibald, Commissioner Simpson, Major A.G. Irvine, and eight witnesses. However, it is important to note that the signatories for the Anishinaabe and the Swampy Cree were Red Eagle (Mis-koo-ke-new, or Henry Prince), Bird Forever (Ka-ke-ka-penais, or William Pennefather), Flying Down Bird (Na-sha-ke-penais), Centre of Bird’s Tail (Na-na-wa-nanan), Flying Round (Ke-we-tay-ash), Whip-poor-will (Wa-ko-wush), and Yellow Quill (Os-za-we-kwun).

The Governor General in Council officially ratified the treaty on 12 September 1871. According to the terms of the treaty, each band was promised a reserve that would be large enough to provide 160 acres for each family of five, or a proportionate amount for smaller or larger families. Additionally, each individual, regardless of age, was to receive a one-time payment, or gratuity, of three dollars. Furthermore, a yearly annuity of $15 per family of five was agreed upon. The government also committed to establishing schools on each reserve and prohibiting the introduction or sale of liquor on reserves.

However, it is crucial to understand that from the Indigenous perspective, the written text of the treaty required the Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree to "cede, release, surrender, and yield up to her Majesty the Queen" a specific tract of land described in detail in the treaty. This land encompassed a significant portion of present-day southeast and south-central Manitoba, including the Red River Valley, and extended north to the lower parts of Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg, as well as west along the Assiniboine River to the towns of Portage la Prairie and Brandon.

Modern-Day Interpretation

In addition to the aforementioned issues, it is important to highlight that Archibald and Simpson failed to include a provision on hunting and fishing rights in the written texts of Treaties 1 and 2, despite Archibald verbally assuring Indigenous peoples that they would retain these rights in the ceded territory. Unfortunately, in the following decades, the settler government of Manitoba began to restrict Indigenous peoples' access to game and fish, disregarding these promises.

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized that the written text alone cannot fully capture the "spirit" of the treaties. The courts now consider the historical context and the likely perceptions of each party involved in the agreement. Anishinaabe lawyer and author Aimée Craft has pointed out that it is highly unlikely that the Indigenous participants understood the concept of "surrender," especially when the Euro-Canadian negotiators repeatedly assured them that they would still be able to utilize the natural resources within the surrendered territory. This assurance seems contradictory to the notion of surrender.

Likewise, it is possible that the Euro-Canadian negotiators failed to comprehend the perspectives rooted in Anishinaabe concepts of law, or inaakonigewin, that the Indigenous participants brought to the treaty. Craft has explained how Anishinaabe beliefs in a sacred relationship with the land make it challenging to discuss ownership or surrender. The Indigenous perspective on the kinship terms frequently used by the Euro-Canadian negotiators, such as referring to the Queen as "the Great Mother," likely involved maintaining a greater level of autonomy and equality in relation to Europeans than Archibald, Simpson, or the emerging policies of the federal government would allow. Similarly, the Euro-Canadian negotiators would not have fully grasped the ideologies of sharing land and respecting each other's livelihoods that the Anishinaabe brought to the negotiating table. Based on these mutual misunderstandings, it is likely that the interpretation of Treaties 1 and 2, like many others, will continue to be a subject of debate.

Negotiations

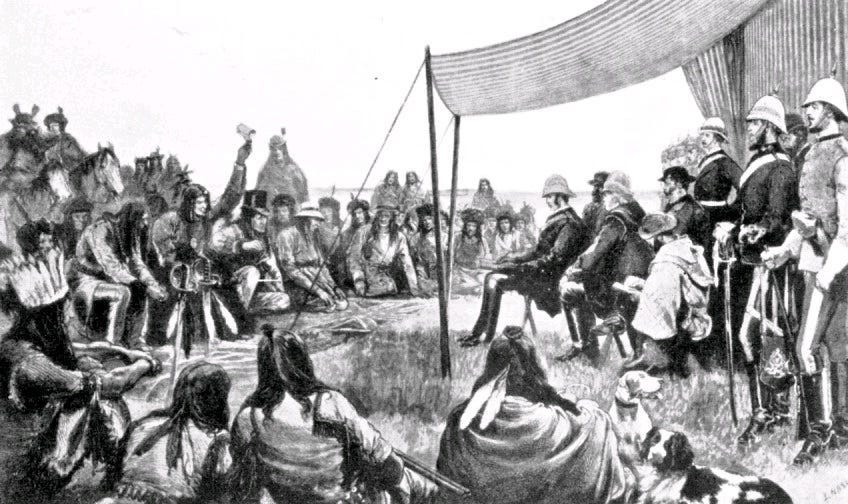

The negotiations for Treaty 1 commenced on 27 July 1871, following the establishment of an impressive camp by approximately 1,000 Indigenous attendees, including men, women, and children. The camp consisted of around 100 tents arranged in a semi-circle around Fort Garry. James McKay, a Métis member of Manitoba's Executive Council, served as the interpreter during the negotiations.

Treaty 1 stands out among the Numbered Treaties due to the unique circumstance that daily transcripts of the lengthy eight-day negotiation were published by The Manitoban, a Winnipeg weekly. In his opening statements, Archibald reassured the attendees that Queen Victoria, whom he referred to as the "Great Mother," desired fair treatment for Indigenous peoples. He expressed that while the Queen hoped for Indigenous peoples to embrace agriculture, she would not impose drastic changes upon them. Archibald attempted to introduce the concept of reserves but emphasized that Indigenous people would still have the freedom to maintain their traditional ways of life on the surrendered territory until a vaguely defined future time when those lands were deemed "needed for use."

our Great Mother, therefore, will lay aside for you ‘lots’ of land to be used by you and your children forever. She will not allow the white men to intrude upon these lots. She will make rules to keep them for you, so that as long as the sun shall shine, there shall be no Indian who has not a place that he can call his home […]

Till [sic] these lands are needed for use, you will be free to hunt over them, and make all the use of them which you have made in the past. But when lands are needed to be tilled or occupied, you must not go on them any more.

Lieutenant-Governor Archibald

After two days of deliberation, the Indigenous negotiators returned with a list of demands that Archibald and Simpson deemed "exorbitant." They requested reserves in proportion to "three townships per Indian," which Archibald estimated would have amounted to about two-thirds of the province. Archibald expressed his belief to Secretary of State Howe in a letter on 29 July that the Indigenous negotiators had false ideas about reserves, thinking that large tracts of land would be set aside for them as hunting grounds, including timber lands that they could sell as if they were the owners of the soil.

Archibald insisted that he was willing to provide reserves based on the formula of 160 acres per family of five, which was consistent with the provisions for homesteads for white settlers outlined in the Dominion Lands Act, of which Archibald was involved in creating. However, it is evident from the proceedings that any explanation was muddled by Archibald and Simpson's repeated assurances that the signatories would still be able to use the land in the surrendered territory for traditional activities like hunting, trapping, and fishing. Furthermore, the lieutenant-governor further confused matters by casually promising that the land requirements of future generations would be met "further West" and that if the reserves were found to be too small, the government would sell the land and provide the Indigenous peoples with land elsewhere.

Amidst these somewhat careless reassurances, there was an underlying threat. Archibald informed the Indigenous negotiators that whether they liked it or not, immigrants would come and populate the country, and now was the time for them to reach an agreement that would secure homes and annuities for themselves and their children.

One Indigenous negotiator pointed out that granting 160 acres to both Indigenous and Euro-Canadian peoples was not equitable, as the typical settler had the capital to establish a farm. Another individual, Ay-ee-ta-pe-pe-tung, became disillusioned with the proceedings and threatened to "go home without treating," even if it meant that the Queen's subjects would encroach on his land. "Let them rob me," Ay-ee-ta-pe-pe-tung asserted.

The impasse was finally broken on the last day of negotiations, 2 August. After six days, Henry Prince questioned how they would be treated and how the Queen would help them learn to cultivate the land. He pointed out that they couldn't work the land with their fingers and asked what assistance they would receive if they settled down. According to the Manitoban, the Indigenous negotiators were reassured by the Crown's representatives that the Queen was willing to help them in every way. In addition to providing land and annuities, she would also provide a school and a schoolmaster for each reserve, as well as ploughs and harrows for those who wished to cultivate the soil.

On 3 August 1871, Treaty 1 was signed at Fort Garry. The tense and challenging eight-day negotiations highlighted the difficulty in reaching mutual understanding on Euro-Canadian concepts such as "reserves" and "surrender." It also demonstrated that the Indigenous negotiators fought hard to secure the reserves they needed for the future. Contrary to the notion of a benevolent government acting with foresight to prevent unrest, the treaty negotiations, as argued by historian D.J. Hall, were poorly handled by an ill-prepared government and its officials. It was the Indigenous participants who forced changes to the government's plan and raised the issues that would arise in subsequent treaties, focusing on how Indigenous people would secure the resources necessary for their future.

Darren Grimes

Our Home and (Native?) Land - Part 7 The Inherent rights of the Anishinaabe People Prior to European Contact

The territory covered by Treaty 2 extends beyond its current boundaries. According to the original text, it stretches north of Treaty No.1 territory

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indigenous Opinions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.