The Mishkeegogamang First Nation community is comprised of Ojibway people, who are part of the Algonquian language group. This group includes Cree people and up to thirty other cultures, each with their own unique languages and dialects.

According to the people of Mishkeegogamang, their ancestors originated from the Great Lakes area and were not believed to have migrated over the Bering Strait to populate North America. Instead, they believe that their people have always been in this area, placed here by the Creator. The Ojibway people identify themselves as Anishinaabe, which comes from the root words ani meaning "from whence," nishina meaning "lowered," and aabe meaning "the male of the species." Legends say that the Creator made man from the four sacred elements and then lowered him to the earth.

In addition to facing continuing overreach onto their reserves, the Mishkeegogamang people have been dealing with ongoing issues related to mining and lumber companies that hold licenses to operate on their traditional lands outside of the reserve. Although the treaty granted the people the right to hunt and fish on those lands in perpetuity, this right is denied to them if the lands are destroyed by mining and lumbering activities. While these companies promise job opportunities, these have often turned out to be temporary and, more often than not, given to white people instead of the local population. Those who hold a traditional and long-term perspective argue that the companies are essentially hiring the people to exploit their own land, ultimately leaving them with nothing

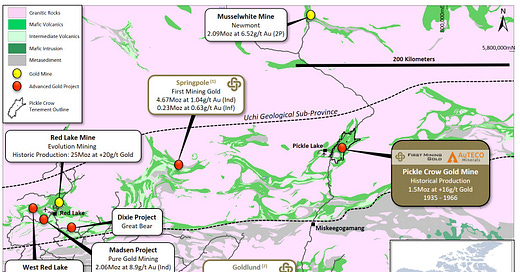

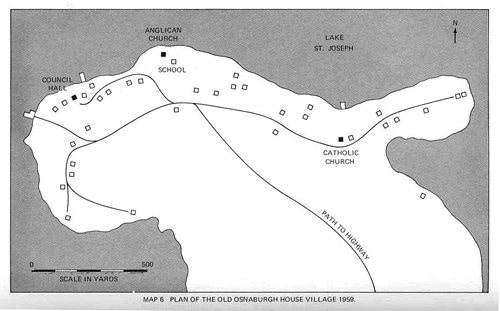

In 1929, gold was discovered north of Osnaburgh (Mishkeegogamang), leading to the establishment of the Pickle Crow Gold Mine and the Central Patricia Gold Mine. By 1934, these mines had requested that the Ontario government provide them with hydro at their sites, which were located about 25 miles north of Osnaburgh House. In response, Ontario Hydro built a dam and installed a generator at Rat Rapids in 1934-35, a site that had been deliberately excluded from the reserves due to its potential for hydro power. Unfortunately, the water began to rise in March 1935, causing significant damage to the reserve. Homes, gardens, and gravesites along the shores of Lake St. Joseph were washed away, and band members were not given any notice of the flooding

Representatives from Hydro and Indian Affairs assessed the damage to individual property at $845.00 and divided this sum among 18 individuals who were paid on the spot. Additionally, $1,425.00 was paid to Indian Affairs for timber losses on flooded acreage, and $100.00 was paid in compensation for the flooded council house. However, the Hudson's Bay Company received $17,000.00 in compensation for the flooding, despite their relocation costs totalling only $9,500.00. This discrepancy remains unexplained.

The primary issue for the Mishkeegogamang band in the hydro developments was the lack of consultation or communication regarding the developments. Due process, as outlined in Treaty Number Nine and the law, was not followed. For instance, Hydro compensated the government $425.00 for timber loss along the power line, but there is no record of the band consenting to or being consulted about the transmission line.

Around the same time as the Rat Rapids hydro development, mining companies were pushing to transport goods from the rail line at Hudson through Lac Seul via the Root River into Lake St. Joseph. The Ontario government believed that this would improve transportation in northern Ontario and agreed to pay half the cost.

Three timber crib dams were constructed along the transportation route, and the bed of Root Creek was widened. A dock was also built at Dog Hole Bay to facilitate transportation. To complete the route, Pickle Lake mining companies, along with the federal and provincial governments, pushed a road through the reserve from the end of Dog Hole Bay to Pickle Lake.

Once again, the people of Mishkeegogamang were not consulted on the plans, despite the fact that the dams would raise the lake by three feet and equipment and supplies would be landed at Dog Hole Bay, which was located on the Reserve itself. A 1953 petition by the band to Indian Affairs highlights their frustration with developments over which they had no control. "There are always certain subjects at Treaty payments," reads the petition, "that are not entirely clear to us because we have no one sufficiently competent to interpret for us. First on our list is about our flooded lands, rice beds, timber, and the graves of our beloved. We feel we have not been sufficiently compensated for these, and we want a satisfactory explanation." Unfortunately, such explanations were often slow to arrive.

For many years, Ontario Hydro had been planning to divert the water of Lake St. Joseph, which typically flowed into the Albany River, into the Root River and from there into Lac Seul. This diversion would move water into the English River and Winnipeg River systems, providing more hydro power to western Ontario and eastern Manitoba. However, this would cause significant fluctuations in water levels in Lake St. Joseph and reduce the amount of water flowing into the Albany River.

By 1957, the generators at Rat Rapids were no longer being used to produce hydro, so the dams were converted to sluiceways to regulate the flow of water westward. Hydro began diverting water from Lake St. Joseph on November 1, 1957. Reserve land above the natural high water mark was alternately drained and flooded, altering the vegetation and fish and wildlife habitat that had been established since the 1935 flooding. This increased the effect of erosion and dislodged shoreline debris into the lake. The flow of the Albany River was reduced, negatively impacting hunting and fishing. Fishermen had to frequently move their nets due to the varying water levels, which was a time-consuming process and required constant net repair. The cultivation of wild rice in the area also came to an end since wild rice cannot tolerate irregular water levels. The fluctuation in water levels continues to this day.

More recently, a $95-billion lawsuit launched by the Treaty 9 bands could be far-reaching, potentially affecting many treaties signed in the late 19th and early 20th century. The lawsuit argues that the Canadian government has neglected its responsibilities for over a century by not granting it the lands it requested and by allowing hydro development to flood ancestral lands. The lawsuit was launched in response to moves by the provincial government to weaken environmental rules for mining, and the refusal of Ontario Premier Doug Ford to engage with several Nations affected by the Ring of Fire proposal. NDP MP Charlie Angus has warned that the Ford government is jeopardizing a once-in-a-generation opportunity and has called on the federal government to ensure that sustainability and the duty to consult remain at the heart of the critical minerals strategy.

Darren Grimes

Our Home and (Native?) Land - Part 5

The numbered Treaties

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Indigenous Opinions to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.