Nation to Nation?

In Canada today, there are three groups legally barred from property ownership: children, the mentally incompetent, and First Nations people residing on reserves.

Conflict is on the horizon, perhaps a long time coming. Those who believe reconciliation can be achieved through symbolic gestures like blanket exercises or cultural awareness training are sadly mistaken. Reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous peoples requires more than superficial gestures—it demands confronting hard truths, rectifying injustices, and fundamentally reshaping lands, laws, policies, and societal norms.

Under the Indian Act, First Nations individuals living on reserves are stripped of basic property rights, akin to children. They are denied the ability to own land, build equity, or control their property—a profound injustice that no political party in the history of the country has adequately addressed.

True reconciliation necessitates more than token gestures; it entails acknowledging past wrongs, seeking justice, and reshaping power dynamics. While this process may be painful and disruptive, it is crucial for progress. Granting full property rights to on-reserve members is a vital step toward rectifying historical injustices and fostering economic and social well-being.

The concept of consent lies at the core of this issue. Indigenous peoples have long been denied the right to make decisions about their own lives and lands. Whether through historical atrocities like residential schools or contemporary injustices like the Kinder Morgan pipeline, Indigenous communities have been consistently disregarded.

Today, Indigenous peoples' right to free, prior, and informed consent is at the forefront of Canada's reconciliation agenda. Justin Trudeau pledged to enact UNDRIP and honor Indigenous peoples' authority to refuse. When asked if "no" meant "no," Trudeau affirmed this. This veto authority derives from Indigenous governments' inherent rights over their traditional territories, supported by Indigenous laws, section 35 of Canada's Constitution Act, and international human rights laws. However, Justice Minister Raybould countered that "consent doesn’t mean a veto" for Indigenous peoples.

This impasse persists, with Canada failing to reconcile its laws with Indigenous peoples' right to refuse development projects on their lands. Conflict over mining, forestry, fracking, and pipelines on Indigenous lands will persist. The real test lies in actions on the ground, as seen in past conflicts like Oka and Ipperwash. Will Canada force the Kinder Morgan pipeline against British Columbia and First Nations' will? Will it exclude First Nations who reject land-claims processes? What about those defending their reserves from social workers and police?

True reconciliation demands Indigenous peoples' right to refuse, rejecting discriminatory laws, federal control, racism, violence, child theft, imprisonment, land theft, and environmental destruction. This right is fundamental to our sovereignty, shaping our future relationship with Canada. Waiting for court decisions is not enough; First Nations leaders and citizens must assert and defend their right to refuse now. We signed treaties to evolve alongside our European counterparts, not to lifelong rule and management by its governments. Self governance is a core right of indigenous Canadians and this does not mean self governance within the boundaries predetermined by the state.

Since February 2022, Canada has committed over $2.4 billion in military assistance donations to Ukraine.

“We continue to actively look at what more we can do to support Ukraine. Minister Blair remains in close contact with Ukrainian officials through the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, and on a bilateral basis.

We deeply admire the bravery and courage of Ukrainians who are fighting to defend their independence and freedom, and we will continue to work closely with our Allies and partners to help Ukraine defend its sovereignty and security.”

As of 2023, Canada's foreign aid budget stands at $6.9 billion, marking a significant 15% decrease from the previous year. Amidst the ongoing impacts of COVID-19 and global conflicts, this reduction has sparked criticism from various segments of Canada's civil society, advocating for a substantial increase in the aid budget instead.

The crux of the debate revolves around how global poverty is framed, with concerns raised that the conventional approach may inadvertently exacerbate rather than alleviate the issue.

Traditionally, proponents argue that increasing aid enhances Canada's global presence and foreign policy leverage in a world marked by intense geopolitical competition. Recent instances have underscored this perspective.

In February, 75 Canadian organizations joined forces in an open letter to Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, urging for an increase in international aid funding from the $8.15 billion allocated in the 2022 budget to $10 billion annually by 2025.

The budget released on March 28 includes $1 billion allocated for short-term accommodation and temporary health-care coverage for asylum-seekers and refugees, marking a significant increase compared to previous federal contributions to these provisions.

According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the federal government has provided provinces and municipalities with a cumulative total of $551.6 million since 2017 through its Interim Housing Assistance Program (IHAP) to address asylum-related housing pressures. An additional roughly $136 million was spent between March 20, 2020, and Jan. 31, 2023, on temporary accommodations for migrants crossing illegally at Roxham Road. However, even when combined, these totals average less than $150 million annually.

Quebec received a total of $374 million in reimbursements from Ottawa between 2017 and 2020, averaging about $125 million per year. Discussions are ongoing between Quebec and the federal government regarding reimbursement for migrant-related costs in 2021 and 2022.

In the upcoming fiscal year, the new federal budget proposes a total of $1 billion, split into two allocations: $530 million for IRCC to provide short-term accommodations to asylum-seekers unable to find shelter elsewhere, and another $469 million to offer temporary health-care coverage to asylum-seekers and refugees who are not yet eligible for provincial or territorial health insurance.

November 1, 2023 – Ottawa – Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada is pleased to release details on the Government of Canada’s Immigration Levels Plan for 2024-2026. Following the trajectory of the 2023-2025 Plan, Canada aims to welcome 485,000 new permanent residents in 2024, 500,000 in 2025 and plateau at 500,000 in 2026. This plan prioritizes economic growth, and supports family reunification, while responding to humanitarian crises and recognizing the rapid growth in immigration in recent years. Building on the achievement of a 4.4% target of French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec in 2022, the Plan includes new annual and progressively increasing French-speaking permanent resident targets outside Quebec: 6% in 2024, 7% in 2025 and 8% in 2026.

1/2 a million new Canadians per year while most of Canada’s First Nations resemble 3rd world countries.

Consider this: In Canada today, there are three groups legally barred from property ownership: children, the mentally incompetent, and First Nations people residing on reserves.

Yes, you read that correctly. First Nations individuals who choose to live on reserves are lumped into the same category as minors.

This situation arises from the Indian Act, which dictates that First Nations people don't own their land; it's held for them by the government. Consequently, those living on reserves lack the same property rights as other Canadians. They can't build equity in their homes, leverage them for loans, freely sell their land, or pass down wealth to their children.

Surprisingly, none of the political parties have addressed this issue during the ongoing election campaign, despite research highlighting the positive outcomes of extending property rights to First Nations in Canada.

Studies indicate that granting full property ownership to individuals on reserves would enhance the economic and social well-being of these communities and lead to better housing conditions.

Some First Nations leaders, like Chief LeBourdais of Whispering Pines, support extending full property rights but are constrained by provisions in the Indian Act.

If we aim to improve housing conditions and elevate economic and social well-being in First Nations reserves, we must recognize the benefits of granting full property rights to on-reserve members—a fundamental economic right enjoyed by all other Canadians.

Less than six decades ago, John Diefenbaker extended voting rights to all status Indians. Let's hope that First Nations citizens on reserves won't have to wait as long for full property rights, especially when it's proven to foster prosperity and well-being for those who need it most.

Governments often claim to reject paternalism in their dealings with First Nations, yet they persist in unilaterally imposing their own laws, policies, and solutions. It's high time for Canada to relinquish its role as the savior of Indigenous peoples. A more respectful approach involves bypassing national Aboriginal organizations like the Assembly of First Nations, which are effectively controlled by federal funding, and instead engaging directly with legitimate, rights-holding First Nation governments. Let First Nations chart their own path forward, recognizing that a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. Some First Nations may choose to opt out of certain aspects of the Indian Act, while others may not. Some may prefer municipal-style governing arrangements, while others seek inter-governmental agreements that uphold their sovereignty and jurisdiction across all domains.

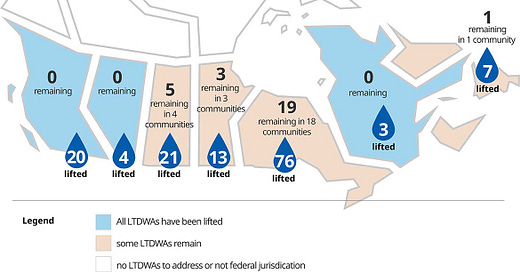

Ending long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities is a multifaceted process that necessitates collaboration between these communities and the Government of Canada. Various actions are undertaken to address water and wastewater issues, including feasibility studies, system design work, interim and permanent repairs, construction of new infrastructure, and enhancements to training and monitoring.

Each community implements initiatives tailored to its specific needs to tackle remaining long-term drinking water advisories. The decision to lift such advisories rests with the community's chief and council, based on recommendations from environmental public health officers.

Different types of drinking water advisories exist in First Nations communities, issued for various reasons and under different circumstances.

While eliminating long-term drinking water advisories is crucial, it is just one aspect of ensuring reliable access to safe drinking water in these communities. This includes investing in water and wastewater infrastructure, ensuring proper staffing and maintenance of water systems, and supporting First Nations' control over water delivery.

The timeline for water and wastewater infrastructure projects varies, with the completion of a new water treatment system, for instance, typically taking 3 to 4 years. As of today, Feb 15, 2024, as per the government of Canada’s own website some 28 boil water advisories exist across First Nations in Canada. I can’t help but wonder how many of those could have been solved if the Government of Canada put as much effort into fixing that and other problems facing reserves like suicide, substance abuse, and loss of culture as it does Ukraine (3 Billion), big pharma (9 billion), consultants (15 billion), and lawyers to cover up its own corruption.

The federal government is no loner interested in negotiating with us nation to nation. The duty to consult has become a novelty.

The government has become unstable.

How will we “Indians” insure that our voice is heard for generations to come?

How will we insure that our treaty lands are still ours for our grandchildrem?

When can we own our own lands?

Thank you Darren, I appreciate these insights.