Five crucial concerns for Indigenous Canadians in 2024

Government officials, researchers, policymakers, and Indigenous leaders often grapple with the overwhelming scope of these problems

DIRE HEALTH DISPARITIES The investigation conducted by the World Health Organization now acknowledges European colonization as a pervasive and foundational determinant of Indigenous health disparities. While numerous Indigenous communities have taken significant steps to enhance health education and awareness, the persisting reality is that Indigenous individuals continue to face elevated risks of illness and premature mortality compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts.

The prevalence of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart conditions is steadily rising within Indigenous populations. These troubling health trends are closely tied to socioeconomic factors, highlighting the inextricable links between income, social determinants, and overall well-being. Moreover, Indigenous children are disproportionately affected by respiratory issues and other infectious diseases, with insufficient housing and crowded living conditions exacerbating these health challenges.

Eugenics, a scientifically discredited and morally reprehensible theory centered on "racial improvement" and "planned breeding," gained popularity in the early 20th century. In Canada, the rise of eugenics coincided with the tightening control of the Indigenous population under the Indian Act. Eugenicists wrongly attributed the high rates of illness and poverty in Indigenous communities to supposed lower racial evolution, deflecting blame from colonialism and Indian Act policies.

During this period, both Alberta (1928) and BC (1933) passed sexual sterilization legislation. While these Sexual Sterilization Acts were repealed in 1972 and 1973, respectively, the damage had already been done. Indigenous individuals, especially Indigenous women, were disproportionately targeted by these acts. They were overrepresented among cases presented for sterilization and among those diagnosed as "mentally defective," leaving them with little agency to refuse the procedure.

This historical characterization of Indigenous women as "unfit" mothers continues to have a lasting impact, contributing significantly to the high number of Indigenous children in Canada's foster care system. Shockingly, despite accounting for only 7.7% of the child population according to Census 2021, Indigenous children make up a staggering 53.8% of those in foster care.

Tragically, forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women persists even today, as evidenced by BILL S-250. This ongoing practice deepens the mistrust Indigenous women have towards the healthcare system and healthcare workers, perpetuating a cycle of injustice and discrimination.

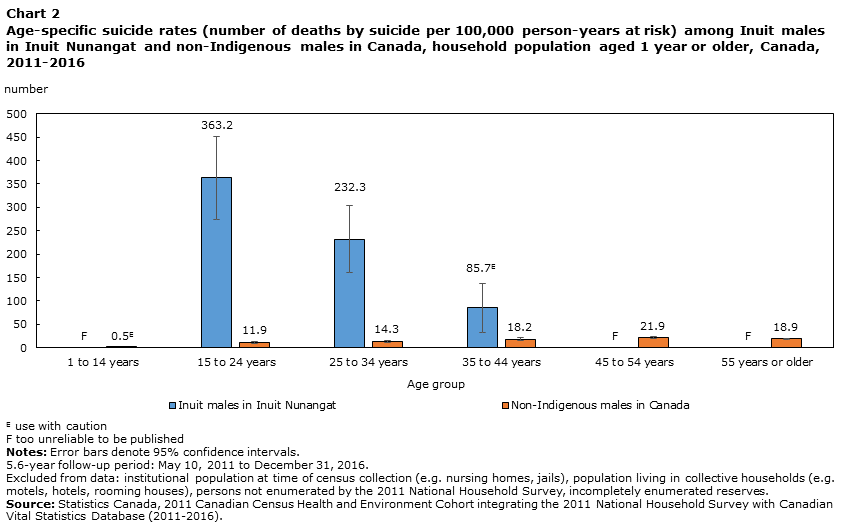

THE TRAGIC BURDEN OF SUICIDE Within the Indigenous population of Canada, there exists an alarming disparity in suicide rates when compared to non-Indigenous communities. Between 2011 and 2016, the suicide rate among First Nations individuals was three times higher than that among non-Indigenous counterparts. Furthermore, a striking difference emerges when analyzing on-reserve and off-reserve populations, with the former experiencing a rate approximately twice as high as the latter. The Métis community also grapples with a troubling statistic, witnessing a suicide rate roughly twice as high as that of non-Indigenous people. However, the most harrowing revelation lies within the Inuit population, where the suicide rate reaches an astounding nine times the national average.

The complex web of factors propelling Indigenous youth and adults toward such tragic decisions is intricately linked to the enduring legacies of colonialism and the assimilation policies encapsulated in the Indian Act. The long-reaching effects of the devastating residential school system, which stands as a symbol of these assimilation policies, cast a heavy shadow of despair and socio-economic disparities over survivors and their families.

In smaller Indigenous communities where many share familial ties, the profound impact of a life lost to suicide reverberates throughout the entire population. When a family member or peer succumbs to suicide, those already grappling with depression, despair, anxiety, hopelessness, and powerlessness may find themselves propelled toward contemplating the same tragic fate. Some communities are haunted by the grim fear that one suicide may trigger a devastating cluster of further self-inflicted deaths.

EMBRACING COMMUNITY HEALING It is essential to tread carefully when discussing suicide rates among Indigenous people, as this approach risks fostering the misconception that suicide is a universal concern across all Indigenous communities. The reality is far more nuanced, with some communities experiencing a lower prevalence of suicide.

An insightful study conducted in Indigenous communities in British Columbia unveiled a noteworthy trend. It revealed that communities characterized by higher levels of "cultural continuity factors," such as self-governance, land claims, education, healthcare, cultural facilities, police, and fire services, reported lower rates of youth suicide when contrasted with those lacking these factors. Additionally, communities with fewer children in the care system and where women hold a majority of positions within local government exhibited a reduced incidence of suicide.

Indigenous communities are incredibly diverse, each unique in its own way. Consequently, the application of uniform intervention strategies, policies, or programs proves ineffective. To address this crisis adequately, it is imperative to involve community leaders and Elders in the development of intervention programs tailored to each community's specific needs.

With approximately 350,000 Indigenous youth poised to reach the age of 15 between 2016 and 2026, it is crucial to recognize that these vulnerable years mark the period when suicide rates peak. As such, there exists a profound responsibility to prevent these young individuals from descending into the abyss of despair, wherein they perceive death as the only conceivable escape.

DISPROPORTIONATE INCARCERATION RATES

A startling disparity looms within the Canadian criminal justice system as Indigenous people find themselves disproportionately ensnared in its web. A staggering 32% of federal inmates identify as Indigenous, a stark contrast to their representation in the broader population, which stands at approximately 5%. This overrepresentation casts a glaring spotlight on the systemic issues ingrained within the criminal justice system.

Notably, Indigenous women bear a disproportionate burden of this overrepresentation, constituting nearly half of the female inmate population within federally run prisons. A somber milestone was reached on April 28, 2022, when the number of incarcerated Indigenous women surged to 50%, mirroring the count of non-Indigenous women behind bars. This disheartening phenomenon can be attributed largely to the presence of systemic bias and racism, which permeate every facet of the criminal justice system.

These inequities manifest in various forms, including the utilization of discriminatory risk assessment tools, ineffective case management, and the sluggish bureaucracy that perpetuates delays and inertia. It is imperative to confront these deep-seated issues head-on to rectify this grievous injustice and strive for a more equitable and just society for all Canadians.

The dire state of Indigenous incarceration rates in Canada cannot be understated; it is an issue that warrants national crisis status. The pervasive flaws ingrained in the justice system serve as a nefarious force that perpetuates a vicious cycle of poverty and marginalization, ensnaring far too many Indigenous individuals in its grip. The gravity of this situation becomes evident when we consider the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's 94 calls to action, of which a staggering 18 are dedicated to issues within the realm of justice. Additionally, three more calls are directed at achieving equity in the legal system, surpassing the commitments made to any other concern.

A stark and unsettling reality emerges from the statistics: Indigenous adults comprised approximately one-third of all adult admissions to provincial and territorial (31%) and federal (33%) custody in 2020, despite representing merely 5% of the Canadian adult population. This disparity is equally disturbing among Indigenous youth, as they accounted for half (50%) of youth admissions to custody during the 2020/2021 period, despite making up approximately 8% of the youth population.

It is disheartening to acknowledge that these distressing statistics are not confined to a specific era; the overrepresentation of Indigenous individuals in incarceration rates has persisted for decades. Despite various measures, ranging from changes to the Criminal Code to rulings by the Supreme Court of Canada, little progress has been made. In fact, the rates of Indigenous incarceration continue to climb. Since 1989, a staggering eleven Royal Commissions or Commissions of Inquiry have delved into the issue of Indigenous justice, either as a direct focus or as part of broader inquiries into Indigenous matters in Canada.

Delving into the annals of the penitentiary system's inception, which commenced with the 1834 Penitentiary Act, reveals a chilling parallel with the residential school system. One of the primary objectives of this early penitentiary system was to reform inmates into industrial workers through methods of "solitary imprisonment, accompanied by well-regulated labor and religious instruction." The prison chaplains held significant authority, serving as both spiritual guides and educators. Upon sentencing, inmates entered imposing edifices where they underwent invasive searches, had their possessions confiscated, their hair forcibly cut short, and their clothing incinerated—a symbolic severance of ties to their previous lives. This hauntingly echoes the practices of the residential school system.

In essence, prisons and residential schools are two sides of the same coin, representing federal institutions that shared a common objective, albeit with differing degrees of direct focus on Indigenous individuals—to sever Indigenous people's connections to their land, history, and culture through the mechanism of assimilation. This dark historical legacy continues to cast a long shadow over Indigenous communities, demanding immediate and comprehensive redress.

LOWER LEVELS OF EDUCATION In the global context, Canada boasts one of the highest levels of educational attainment, a testament to the country's commitment to education. However, the stark reality persists that Indigenous students continue to lag far behind their non-Indigenous counterparts in terms of graduation rates. This educational disparity becomes especially pronounced for Indigenous students residing on reserves.

A comprehensive study conducted by the C.D. Howe Institute reveals the extent of this educational gap. Shockingly, only 48 percent of students living on reserve have managed to complete high school. In stark contrast, 75 percent of Indigenous students living off-reserve have successfully attained their high school diplomas. This disparity underscores the critical need for targeted initiatives and support systems to address the unique challenges faced by Indigenous students on reserves, ensuring equitable access to quality education for all Indigenous youth.

The perplexing disparity in educational outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students in Canada, despite education being considered a fundamental human right, finds its roots in the historical landscape of the country. The key to understanding this paradox lies in the history of Canada, shaped by pivotal legislative acts and policies.

When the British North America Act, later known as the Constitution Act, 1867, was promulgated, it conferred exclusive jurisdiction over "Indians and lands reserved for Indians" to the federal government. Simultaneously, the federal government entered into Treaties 1 through 11, thereby undertaking the responsibility for the education of Indigenous peoples residing within the lands covered by these treaties.

A mere eight years later, in 1876, the federal government consolidated the regulations pertaining to Indigenous peoples into the Indian Act. An illuminating quote from that era reflects the federal government's perspective on its role in Indigenous education:

Our Indian legislation generally rests on the principle that the aborigines are to be kept in a condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State . . . clearly our wisdom and our duty, through education and every other means, to prepare him for a higher civilization by encouraging him to assume the privileges and responsibility of full citizenship

Indigenous students face a multitude of obstacles on their educational journey, and each of these challenges can be directly linked to the historical legacy of residential schools and the Indian Act. These are some of the key factors contributing to the lower educational attainment rates of Indigenous students:

Intergenerational Trauma: The legacy of residential schools has left a profound impact on Indigenous families, leading to intergenerational trauma that can affect students' mental and emotional well-being.

Parental Distrust of the Education System: Many Indigenous parents harbor deep-seated distrust of the education system due to the historical trauma inflicted by residential schools.

Low Parental Educational Attainment: Parents with lower levels of education may struggle to provide adequate support with their children's homework or fully engage in their educational development.

Income Disparities: Lower levels of education often result in lower income, which can lead to issues such as children attending school without proper nourishment.

Overcrowded Housing: Crowded living conditions can compromise students' ability to get adequate rest and create a conducive environment for learning.

Underfunded On-Reserve Schools: On-reserve schools frequently suffer from underfunding, leading to disrepair, insufficient resources like libraries, gyms, and computer labs, and challenges in recruiting and retaining teachers.

Teacher Recruitment and Retention: On-reserve schools often struggle to attract and keep qualified teachers, exacerbating the educational disparities.

Lack of Support Staff: Insufficient funding may result in a shortage of special education instructors, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists, limiting the support available to students with unique needs.

Transportation Issues: Students attending off-reserve schools may face transportation challenges, and missing the school bus can become a significant barrier if parents lack access to a vehicle.

Racism in Off-Reserve Schools: Indigenous students in off-reserve schools can encounter racism, which can have a detrimental impact on their educational experience.

Reluctance to Send Children Away: Some Indigenous families may be reluctant to send their children away to attend school, fearing separation and cultural disconnection.

Lack of Connectivity: Many remote reserves lack adequate internet connectivity, making online learning and access to educational resources difficult.

Each of these challenges underscores the need for comprehensive and culturally sensitive reforms in the education system to address the historical injustices and systemic barriers faced by Indigenous students in Canada.

The issue of funding gaps in education for Indigenous students in Canada is a longstanding and deeply entrenched problem that has contributed to disparities in educational outcomes. Here are some key points regarding this issue:

Historical Underfunding: On-reserve schools, which are primarily attended by Indigenous students, have historically received less funding compared to schools funded by provincial governments. This underfunding has resulted in inadequate resources, outdated facilities, and limited access to extracurricular activities and support services.

Federal Funding Cap: From 1996 to 2015, the federal government imposed a 2% cap on annual funding increases for all First Nation programs and services, including education. This cap remained in place despite the growing Indigenous population and increasing educational needs.

Disparities in Funding: As of 2016, it was estimated that schools on reserves received approximately 30% less funding per student than other schools. This significant funding gap has had a detrimental impact on the quality of education provided to Indigenous students.

Auditor General's Report: In 2018, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada published a damning report highlighting socio-economic gaps on First Nations reserves, including issues related to education. The report underscored the urgent need to address funding inequities.

Revised Funding Model: In 2019, Indigenous Services Canada introduced a revised funding model for on-reserve schools. This model includes guaranteed base funding per student, additional funding for language and culture education, and extra funding based on factors such as remoteness, language, poverty rates, and school size.

Education Jurisdiction Agreements: Education Jurisdiction Agreements are crucial instruments for Indigenous Nations seeking to regain control over the education of their children. These agreements allow Nations to step away from sections of the federal Indian Act (Sections 114 to 122) and take control of various aspects of education, including governance, standards, teacher certification, and decision-making processes.

Self-Governance and Education: The negotiation and implementation of Education Jurisdiction Agreements are part of the broader goal of self-governance for Indigenous Nations. By taking control of education, Nations aim to provide culturally relevant and responsive education that reflects their values and priorities.

Addressing the funding gaps in Indigenous education is essential for improving educational outcomes and addressing the historical injustices that have disproportionately affected Indigenous students. It is a crucial step on the path toward reconciliation and self-determination for Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

INADEQUATE HOUSING

The issue of inadequate housing and crowded living conditions among Indigenous people in Canada is a pressing concern with significant implications for their well-being. Here are key points to consider:

Disproportionate Rates: Indigenous people in Canada experience significantly higher rates of inadequate housing and crowded living conditions compared to the non-Indigenous population. In 2021, approximately 16.4% of Indigenous individuals lived in dwellings needing major repairs, which is nearly three times higher than the rate among non-Indigenous people (5.7%). Additionally, 17.1% of Indigenous people lived in crowded housing, where the housing is not suitable for the number of occupants based on the National Occupancy Standard.

Impact on Health: Inadequate housing can have severe consequences for physical and mental health. Living in homes that require major repairs can lead to exposure to health hazards such as mold, poor heating, and structural issues. Crowded living conditions can increase the risk of the spread of infectious diseases and make it challenging for individuals to maintain privacy and well-being.

Root Causes: The disparities in housing conditions can be traced back to historical factors, including colonial policies, land dispossession, and forced relocations. Indigenous communities often face challenges in accessing safe and affordable housing due to inadequate infrastructure and limited resources.

Overcrowding Challenges: Overcrowding in housing can create multiple challenges, particularly for families and individuals. It can contribute to stress, conflicts, and health issues. Additionally, crowded living conditions can impact children's ability to focus on education and personal growth.

Government Initiatives: Various government initiatives and programs aim to address housing disparities among Indigenous communities. These initiatives often involve investments in housing infrastructure, repairs, and construction of new housing units on reserves.

Community-Led Solutions: Many Indigenous communities are actively working on community-led solutions to improve housing conditions. These initiatives may involve housing development, culturally appropriate housing designs, and sustainable housing practices.

Collaborative Efforts: Addressing inadequate housing and crowded living conditions requires collaborative efforts involving Indigenous communities, government agencies, housing organizations, and other stakeholders. These efforts should be culturally sensitive and responsive to the unique needs and priorities of Indigenous Peoples.

Improving housing conditions for Indigenous communities is essential for promoting their well-being, health, and overall quality of life. Efforts to address this issue should prioritize culturally appropriate solutions and involve the active participation of Indigenous leaders and community members to ensure that housing initiatives are effective and sustainable.

Darren Grimes